Music of Spain

The Music of Spain has a vibrant and long history which has had an important impact on music in Western culture. Although the music of Spain is often associated with traditions like flamenco and the acoustic guitar, Spanish music is in fact incredibly diverse from region to region. Flamenco, for example, is an Andalusian musical genre, which, contrary to popular belief, is not widespread outside that region. In contrast, the music of Galicia has more in common with its Celtic cousins in Ireland and France than with the unique Basque music right next door. Other regional styles of folk music abound in Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Castile, Llión and Asturias. The contemporary music scene in Spain, centered in Madrid and Barcelona, has made strong contributions to contemporary music within the areas of Pop, rock, hip hop, and heavy metal music. Spain has also had an important role within the history of classical music from Renaissance composers like Tomás Luis de Victoria to the zarzuela of Spanish opera to the passionate ballets of Manuel de Falla and the guitarist Pepe Romero.

Contents |

Origins of the Music of Spain

Early history

In Spain, several very different cultural streams came together in the first centuries of the Christian era: the Roman culture, which was dominant for several hundred years, and which brought with it the music and ideas of Ancient Greece; early Christians, who had their own version of the Roman Rite; the Visigoths, an East Germanic tribe who overran the Iberian peninsula in the 5th century; Jews of the diaspora; and eventually the Arabs, or the Moors as the group was sometimes known. Determining exactly which spices flavored the stew, and in what proportion, is difficult after almost two thousand years, but the result was a number of musical styles and traditions, some of them considerably different from what developed in the rest of Europe.

Isidore of Seville wrote about music in the 6th century. His influences were predominantly Greek, and yet he was an original thinker, and recorded some of the first information about the early music of the Christian church. He perhaps is most famous in music history for declaring that it was not possible to notate sounds—an assertion which reveals his ignorance of the notational system of ancient Greece, so that knowledge had to have been lost by the time he was writing.

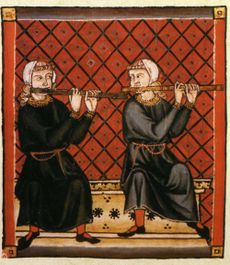

Under the Andalusian Moors, who were usually tolerant of other religions during the seven hundred years of their influence, both Christianity and Judaism, with their associated music and ritual, flourished. Music notation developed in Spain as early as the eighth century (the so-called Visigothic neumes) to notate the chant and other sacred music of the Christian church, but this obscure notation has not yet been deciphered by scholars, and exists only in small fragments. The music of the Christian church in Spain is known as Mozarabic Chant, and developed in isolation, not subject to the enforced codification of Gregorian chant under the guidance of Rome around the time of Charlemagne. At the time of the reconquista, this music was almost entirely extirpated: once Rome had control over the Christians of the Iberian peninsula, the regular Roman rite was imposed, and locally developed sacred music was banned, burned, or otherwise eliminated. The style of Spanish popular songs of the time is presumed to be closely related to the style of Moorish music. Music of the King Alfonso X Cantigas de Santa Maria is considered likely to show influence from Islamic sources. Other important medieval sources include the Codex Calixtinus collection from Santiago de Compostela and the Codex Las Huelgas from Burgos. The so-called Llibre Vermell de Montserrat (red book) is an important devotional collection from the 14th century.

Renaissance and Baroque

In the early Renaissance, Mateo Flecha el viejo and the Castilian dramatist Juan del Encina rank among the main composers in the post-Ars Nova period. Some renaissance songbooks are the Cancionero de Palacio, the Cancionero de Medinaceli, the Cancionero de Upsala (it is kept in Carolina Rediviva library), the Cancionero de la Colombina, and the later Cancionero de la Sablonara. The organist Antonio de Cabezón stands out for his keyboard compositions and mastery.

Early 16th century polyphonic vocal style developed in Spain was closely related to the style of the Franco-Flemish composers. Melting of styles occurred during the period when the Holy Roman Empire and Burgundy were part of the dominions under Charles I(king of Spain from 1516 to 1556), since composers from the North both visited Spain, and native Spaniards travelled within the empire, which extended to the Netherlands, Germany and Italy. Music for vihuela by Luis de Milán, Alonso Mudarra and Luis de Narváez stands as one of the main achievements of the period. The Aragonese Gaspar Sanz was the author of the first learning method for guitar. The great Spanish composers of the Renaissance included Francisco Guerrero and Cristóbal de Morales, both of whom spent a significant portion of their careers in Rome. The great Spanish composer of the late Renaissance, who reached a level of polyphonic perfection and expressive intensity equal or even superior to Palestrina and Lassus, was Tomás Luis de Victoria, who also spent much of his life in Rome. Most Spanish composers returned home late in their careers to spread their musical knowledge in their native land or at the service of the Court of Philip II at the late 16th century.

18th to 20th centuries

By the end of the 17th century the "classical" musical culture of Spain was in decline, and was to remain that way until the 19th century. Classicism in Spain, when it arrived, was inspired on Italian models, as in the works of Antonio Soler. Some outstanding Italian composers as Domenico Scarlatti or Luigi Boccherini were appointed at the Madrid court. The short-lived Juan Crisóstomo Arriaga is credited as the main beginner of Romantic sinfonism in Spain.

Fernando Sor, Dionisio Aguado, Francisco Tárrega and Miguel Llobet are known as composers of guitar music. Fine literature for violin was created by Pablo Sarasate and Jesús de Monasterio.

Zarzuela, a native form of light opera, is a secular musical form which developed in the early 17th century. Some beloved zarzuela composers are Ruperto Chapí, Federico Chueca and Tomás Bretón.

Musical creativity mainly moved into areas of folk and popular music until the nationalist revival of the late Romantic era. Spanish composers of this period include Felipe Pedrell, Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Joaquín Turina, Manuel de Falla, Jesús Guridi, Ernesto Halffter, Federico Mompou, Salvador Bacarisse, and Joaquín Rodrigo.

Flamenco

Flamenco is an Andalusian traditional folk music. It consists of three forms: the song (cante), the dance (baile) and the guitar (guitarra). The first reference dates back to 1774, from Cadalso's "Cartas Marruecas". Cádiz, Jérez de la Frontera and Triana rank among the main sources in Flamenco uprising. Some early writers thought that it could be a descendant of musical forms left by Moorish inhabitants during the 8th to 15th centuries. Influences from the Byzantine church music, Egypt, Pakistan and India have also been claimed for shaping the music. On the other hand, most lyrics are strongly based on the traditional, folk poetry found all over the Iberian peninsula.

Flamenco sprang from the lower levels of Andalusian society and thus lacked the prestige of art forms among the middle and higher levels. The Muslim Moors, the Gypsies and the Jews were all persecuted.The Muslim Moors (moriscos) and Jews were expelled by the Spanish Inquisition in 1492. Gypsies have been fundamental in maintaining this art form, but having an oral culture, their folk songs were passed on to new generations by repeated performances. Non-gypsy Andalusian poorer classes, in general, were also illiterate.

Lack of interest from historians and musicologists. "Flamencologists" have usually been flamenco connoisseurs of no specific academic training in the fields of history or musicology. They have tended to rely on a limited number of sources (mainly the writings of 19th century folklorist Demófilo),[1] and notes by foreign travellers. Bias has also been frequent in flamencology. This started to change in the 1980s, when flamenco slowly started to be included in music conservatories, and a growing number of musicologists and historians began to carry out more rigorous research. Since then, some new data have shed new light on it. (Ríos Ruiz, 1997:14). Main stream scholars recognize all these early influences but consider flamenco as an earlier 19th century performance stage music as tango, rebetiko or fado.

Regional folk music

Spain's autonomous regions have their own distinctive folk traditions. There is also a movement of folk-based singer-songwriters with politically active lyrics, paralleling similar developments across Latin America and Portugal. While the bulk of today's Spanish traditional music can only be traced as far back as early 19th century, a handful of ritual religious music can be dated back to renaissance and middle age eras. So-called Iberian, Celtic, Roman, Greek or Phoenician music influence only exists in the minds of fanciful dilettanti. Singer and composer Eliseo Parra (b 1949) has recorded folk music of the Basques and of Salamanca.

Andalusia

Though Andalusia is best known for flamenco music (see below for more information), folk music features a strong musical tradition for gaita rociera (tabor pipe) in Western Andalusia and a distinct violin and plucked-strings band known as panda de verdiales in Málaga.

The region has also produced singer-songwriters like Javier Ruibal and Carlos Cano, who revived a traditional music called copla. Catalan Kiko Veneno and Joaquín Sabina are popular performers in a distinctly Spanish-style rock music, while Sephardic musicians like Aurora Moreno, Luís Delgado and Rosa Zaragoza keep alive-and-well Andalusian Sephardic music.

Aragon

Jota, popular across Spain, could have historical roots in the Southern part of Aragon. Jota instruments include the castanets, guitar, bandurria, tambourines and sometimes the flute. Aragonese music can be characterized by a dense percussive element, that some tried to attribute as an inheritance from North African Berbers. The guitarro, a unique kind of small guitar also seen in Murcia, seems Aragonese in origin. Besides its music for stick-dances and dulzaina (shawm), Aragon has its own gaita de boto (bagpipes) and chiflo (tabor pipe). As in the Basque country, Aragonese chiflo can be played along to a chicotén string-drum (psaltery) rhythm.

Asturias, Cantabria and Galicia

Northwest Spain (Galicia, Asturias and Cantabria) is home to a distinct musical tradition which bears a strong Celtic stamp. The region's signature instrument is the gaita, a bagpipe. This instrument is often accompanied by a snare drum called the tamboril, and played in processional marches. Other instruments include the requinta, a kind of fife; as well as harps, fiddles, rebec and zanfona (hurdy-gurdy). The music itself runs the gamut from uptempo muinieras to stately marches. As in the Basque Country, Cantabrian folk music features intrincate arch and stick dances but tabor pipes does not play such a predominant role.

All the languages in this area are of Latin origin but local festivals celebrating the area's so-called Celtic influence are common, with Ortigueira's Festival del Mundo Celta being especially important. Drum and bagpipe groups range among the most beloved kind of Galician folk music, and include popular bands like Milladoiro. Groups of pandereteiras are another traditional set of singing women that play tambourines. Bagpipe virtuoso Carlos Núñez is an especially popular performer.

Galician folk music includes characteristical alalas songs. Alalas, that may include instrumental interludes, are believed to be chant-based popular songs with a long history.

Asturias is also home to popular musicians such as José Ángel Hevia (a virtuoso bagpiper) and famous Celtic group Llan de Cubel. Circle dances using a 6/8 tambourine rhythm are also a hallmark of this area. Vocal asturianadas show melismatic ornamentations similar to those of other parts of the Iberian Peninsula. There are many festivals, such as "Folixa na Primavera" (April, in Mieres), "Intercelticu d'Avilés" (Interceltic festival of Avilés, in July), as well as many "Celtic nights" in Asturias.

Balearic Islands

In the Balearic Islands, Xeremiers or colla de xeremiers is a traditional ensemble that consists of flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe) and xeremies (bagpipes). Majorca's Maria del Mar Bonet was one of the most influential artists of nova canço, known for her political and social lyrics. Tomeu Penya, Biel Majoral, Cerebros Exprimidos and Joan Bibiloni are also popular.

Basque Country

The Basques have a unique language, unrelated to any other in the world except according to some uncertain theories. The most popular kind of Basque folk music is called after the dance trikitixa, which is based on the accordion and tambourine. Popular performers are Joseba Tapia and Kepa Junkera. Very appreciated folk instruments are txistu (similar to Occitanian galoubet recorder), alboka (a double clarinet played in circular-breathing technique, similar to other Mediterranean instruments like launeddas) and txalaparta (a huge xylophone, similar to the Romanian toacă and played by two performers in a fascinating game-performance). As in many parts of the Iberian peninsula, there are ritual dances with sticks, swords and vegetal arches. Other popular dances are fandango, jota and 5/8 zortziko.

Basques on both sides of the Pyrenees have been known for their singing since the Middle Ages, and a resurgence of Basque cultural nationalism at the end of the 19th century led to the establishment of large Basque-language choirs that helped preserve their language and songs. Even during the persecution of the Francisco Franco era (1939–1975), when the Basque language was outlawed, folk songs and dances were defiantly preserved in secret, and today both traditional and pop sounds flourish in the Basque country of Spain.

Canary Islands

In the Canary Islands, Isa, a local kind of Jota, is now popular, and Latin American musical (Cuban) influences are quite widespread, especially in the presence of the charango (a kind of guitar). Timple, the local name for ukulele / cavaquinho, is commonly seen in plucked string bands. A popular set in El Hierro island consists of drums and wooden fifes (pito herreño). Tabor pipe is customary in some ritual dances in Tenerife island.

Castile, Madrid and León

A large inland region, Castile, Madrid and Leon had predominantly Celtiberian and Celtic cultural background before the Roman rule. The area has been a melting pot, however, and Gypsies, Moors, Portuguese, Jewish, Roman, Visigothic and sources could have left a mark on the region's music.

Jota is popular, but uniquely slow in Castile and Leon. Instrumentation also varies here much from the one in Aragon. Northern León, that shares a language background with the Portuguese town of Miranda do Douro and Asturias, also has Galician influences. There are also gaita (bagpipe) and tabor pipe traditions. The Maragatos people, of uncertain origin, have a unique musical style and live in Leon, around Astorga. All over Castile there is also a strong tradition of dance music for dulzaina (shawm) and rondalla groups. Popular rhythms include 5/8 charrada and circle dances, jota and habas verdes. As in many other parts of the Iberian peninsula, ritual dances include paloteos (stick dances). Salamanca is known as the home of tuna, a serenade played with guitars and tambourines, mostly by students dressed in medieval clothing. Madrid is known for its chotis music, a local variation to the European tradition of 19th century schottische dance. Flamenco is also popular among some urbanites.

Catalonia

Though Catalonia is best known for sardana music played by a cobla, there are other traditional styles of dance music like ball de bastons (stick-dances), galops, ball de gitanes. Music takes forefront personality in cercaviles and celebrations similar to Patum in Berga. Flabiol (a five-hole tabor pipe), gralla or dolçaina (a shawm) and sac de gemecs (a local bagpipe) are traditional folk instruments that make part of some coblas.

Catalan gipsies have created their own style of rumba called rumba catalana which is a popular style that's similar to flamenco, but not technically part of the flamenco canon. The rumba catalana originated in Barcelona when the rumba and other Afro-Cuban styles arrived from Cuba in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Catalan performers adapted them to the flamenco format (swiping the Cuban cajon, or "rumba box," in the bargain) and made it their own. Though often dismissed by aficionados as "fake" flamenco, rumba catalana remains wildly popular to this day.

Sevillanas are even more intimately related to flamenco, and most flamenco performers have at least one classic sevilliana in their repertoire. The style originated as a Medieval Castilian folk dance, called the seguidilla, which was slowly "flamenconized" during the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, the lively couples dance is popular in most parts of Spain, but most often associated with the city of Sevilla's famous Easter feria.

The havaneres singers remain popular. Nowadays, young people cultivate Rock Català popular music, as some years ago the Nova Cançó was relevant.

Extremadura

Having long been the poorest part of Spain, Extremadura is a largely rural region known for Portuguese influence on its music. As in Northern regions of Spain, there is a rich repertoire for tabor pipe music. The zambomba drum (similar to Portuguese sarronca or Brazilian cuica) is played by pulling on a rope which is inside the drum. It is found throughout Spain. The jota is common, here played with triangles, castanets, guitars, tambourines, accordions and zambombas.

Murcia

Murcia is a region in the South East of the peninsula which has strong Moorish influences, as well as Andalusian. Flamenco and guitar-accompanied cante jondo is especially associated with Murcia as well as rondallas (plucked-string bands). Religious songs as the Auroras are traditionally sung a capella, sometimes accompanied by the sound of church bells, and Cuadrillas are festive songs primarily played at holidays like Christmas.

Navarre and La Rioja are small regions with diverse cultural elements. Northern Navarre is Basque in language, while the Southern section shares more Aragonese features. The jota is also known in both Navarre and La Rioja. Both regions have rich dance and dulzaina (shawm) traditions. Txistu (tabor pipe) and dulzaina ensembles are very popular to public celebrations in Navarra.

Valencia

Traditional music from Valencia is characteristically mediterranean in origin. Valencia also has its local kind of Jota. Moreover, Valencia has a high reputation for musical innovation, and performing brass bands called bandes are common, with one appearing in almost every town. Dolçaina (shawm) is widely found. Valencia also shares some traditional dances with other Iberian areas, like for instance, the ball de bastons (stick-dances). The group Al Tall is also well-known, experimenting with the Berber band Muluk El Hwa, and revitalizing traditional Valencian music, following the Riproposta Italian musical movement.

Pop Music

Although Spanish pop music is currently flourishing, the industry suffered for many years under Francisco Franco's regime, with few outlets for Spanish performers during the 1930s through the 1970s. Regardless, American and British music, especially rock and roll, had a profound impact on Spanish audiences and musicians. The Benidorm International Song Festival,founded in 1959 in Benidorm, became an early venue where musicians could perform contemporary music for Spanish audiences. Inspired by the Italian San Remo Music Festival, this festival was followed by a wave of similar music festivals in places like Barcelona, Majorca and the Canary Islands. Many of the major Spanish pop stars of the era rose to fame through these music festivals. An injured Real Madrid player-turned-singer, for example, became the world-famous Julio Iglesias.

During the 1960s and early 1970s, tourism boomed, bringing yet more musical styles from the rest of the continent and abroad. However, it wasn't until the 1980s that Spain's burgeoning pop music industry began to take off. During this time a cultural reawakening known as La Movida Madrileña produced an explosion of new art, film and music that reverberates to this day. Once derivative and out-of-step with Anglo-American musical trends, contemporary Spanish pop is as risky and cutting-edge as any scene in the world, and encompasses everything from shiny electronica and Eurodisco, to homegrown blues, rock, punk, ska, reggae and hip-hop to name a few. Artist like Alejandro Sanz, have become successful internationally, selling million of albums worldwide and winning major music awards such as the coveted Grammy Award.

Ye-Yé

From the English pop-refrain words "yeah-yeah", ye-yé was a French-coined term which Spanish language appropriated to refer to uptempo, "spirit lifting" pop music. It mainly consisted of fusions of American rock from the early 60s (such as twist) and British beat music. Concha Velasco, a talented singer and movie star, launched the scene with her 1965 hit "La Chica Ye-Yé", though there had been hits earlier by female singers like Karina (1963). The earliest stars were an imitation of French pop, at the time itself an imitation of American and British pop and rock. Flamenco rhythms, however, sometimes made the sound distinctively Spanish. From this first generation of Spanish pop singers, Rosalia's 1965 hit "Flamenco" sounded most distinctively Spanish.

Performers

Some of Spain's most famous musicians and bands are:

Alternative / indie bands

- La Buena Vida

- Los Planetas

- Los kendala

- Las Ryano

Cantautores

- Luis Eduardo Aute

- Paco Ibáñez

- José Antonio Labordeta

- Lluís Llach

- Joaquín Sabina

- Joan Manuel Serrat

- Víctor Manuel

Electropop bands

- Aviador Dro

- Fangoria

- Hidrogenesse

- The Pinker Tones

Flamenco, New Flamenco or copla singers, guitarists and bands

- Concha Buika

- El Fary

- Camarón de la Isla

- María Jiménez

- Rocío Jurado

- Ketama

- Paco de Lucía

- Pepe de Lucía

- Antonio Molina

- Enrique Morente

- Ojos de Brujo

- Isabel Pantoja

- Domingo DeGrazia

- Testicals

Pop music or ballad singers and bands

- Alejandro Sanz

- Ana Torroja

- Álex Ubago

- Amaia Montero

- Amaral

- David Bisbal

- Miguel Bosé

- Café Quijano

- Chenoa

- Conchita

- Sergio Dalma

- Dúo Dinámico

- Edurne

- El Sueño de Morfeo

- Fórmula V

- Enrique Iglesias

- Julio Iglesias

- La Oreja de Van Gogh

- La Quinta Estación

- Rosa López

- Mecano

- Mónica Naranjo

- Nena Daconte

- Presuntos Implicados

- Raphael

- Paloma San Basilio

- Marta Sánchez

- Mil i Maria

Pop rock or rock singers and bands

- Enrique Bunbury

- Celtas Cortos

- Dover

- Duncan Dhu

- El Canto del Loco

- El Último de la Fila

- Estopa

- Héroes del Silencio

- Hombres G

- Jarabe de Palo

- Las Ketchup

- Loquillo

- Los Bravos

- Los Rodríguez

- Los Toreros Muertos

- Mojinos Escozíos

- Nacha Pop

- Pereza

- Pignoise

- Radio Futura

- Miguel Ríos

- Siniestro Total

- Tequila

- Triana

Other genres

- Paloma Berganza (chanson singer)

- Rocío Dúrcal (ranchera singer)

Also from Spain was the famous trio of singing clowns Gaby, Fofó y Miliki.

Sample

- Download recording of "Venid pastores", a Spanish-American Christmas song from the Library of Congress' California Gold: Northern California Folk Music from the Thirties Collection; performed by Aurora Calderon on April 10, 1939 in Oakland, California

References

- Fairley, Jan "A Wild, Savage Feeling". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 279–291. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0

- Fairley, Jan with Manuel Domínguez. "A Tale of Celts and Islanders". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 292–297. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0

- Alan Lomax: Mirades Miradas Glances. Photos and CD by Alan Lomax, ed. by Antoni Pizà (Barcelona: Lunwerg / Fundacio Sa Nostra, 2006) ISBN 84-9785-271-0

External links

- A collection of spanish music videos www.grattia.com

- AlejandroSanz4EnglishSpeakers A collection of translated songs from one of Spain's most famous singers.

- Bloomingdale School of Music Piano Project: Sonidos de Espana/Music of Spain - extensive monthly features on the history of Spanish music.

- Spanish language music Traditional and contemporary Spanish-language music, with genre descriptions, representative artists, CDs & audio samples.

- MIDI samples of traditional music from the Iberian peninsula * Mirror site

- "Autocantantes" Song Protest Alternative Spanish Music * Artisan Music from Madrid.

- Learn Spanish with songs Morkol will help you to learn Spanish with songs. Listen to the songs while you read the lyrics.

- Foundation for Iberian Music at The City University of New York

- Spainmusictv.com Spanish music videos

- Spanish Folk Music in Havana (Photo Album)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||